One spring evening in the year 1859, when I was a boy of eleven, I said goodbye to my father at the gate of the Cadets' Academy at Wahlstatt, in Silesia. I was bidding farewell not to my dear father only, but to my whole past life. Overwhelmed by that feeling, I could not prevent the tears from stealing from my eyes. I watched them fall on my uniform. "A man can't be weak and cry in this garb," was the thought that shot through my head. I wrenched myself free from my boyish anguish and mingled, not without a certain apprehension, among my new comrades.

That I should be a soldier was not the result of a special decision. It was a matter of course. Whenever I had had to choose a profession, in boys' games or even in thought, it had always been the military profession. The profession of arms in the service of King and Fatherland was an old tradition in our family.

Our stock — the Beneckendorffs — came from the Altmark, where it had originally settled in the year 1289. From there, following the trend of the times, it found its way through the Neumark to Prussia. There were many who bore my name among the Teutonic Knights who went out, as Brothers of the Order, or "War Guests," to fight against heathendom and Poland. Subsequently our relations with the East became ever closer as we acquired landed property there, while those with the Marches became looser and ceased altogether at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

We first acquired the name "Hindenburg" in the year 1789. We had been connected with that family by marriage in the Neumark period. Further, the grandmother of my great-grandfather, who served in the von Tettenborn Regiment and settled at Heiligenbeil in East Prussia, was a Hindenburg. Her unmarried brother, who once fought as a colonel under Frederick the Great, bequeathed to his great-nephew, on condition that he assumed both names, his two estates of Neudeck and Limbsee in the district of Rosenberg, which had originally fallen to Brandenburg with the East Prussian inheritance but had subsequently been assigned to West Prussia. This received King Frederick William II's consent, and the name "Hindenburg" came into use through the abbreviation of the double name.

As a result of this bequest the estate at Heiligenbeil was sold. Further, Limbsee had to be disposed of as a matter of necessity after the War of Liberation. Neudeck is still in the possession of our family today. It belongs to the widow of one of my brothers who was not quite two years younger than I, so that the course of our lives kept us in close and affectionate touch. He too was a cadet and was permitted to serve his King as an officer for many years in war and peace.

During my boyhood my grandparents were living at Neudeck. They now rest in the cemetery there with my own parents and many others who bear my name. Almost every year we paid my grandparents a visit in the summer, though in the early days it meant difficult journeys by coach. I was immensely impressed when my grandfather, who had served in the von Langen Regiment after 1801, told me how in the winter of 1806-7 as Landschaftsrat he had visited Napoleon I in the castle of Finckenstein nearby to beg him to remit the levies, but had been coldly turned away. I also heard how the French were quartered in and marched through Neudeck. My uncle, von der Groeben, who had settled on the Passarge, used to tell me of the battles that were fought in this region in 1807. The Russians pressed forward over the bridge, but were driven back again. A French officer who was defending the manor with his men was shot through the window of an attic. A little more, and the Russians would have been crossing that bridge again in 1914!

After the death of my grandparents my father and mother went to Neudeck in 1863. There, after a removal which was over familiar ground, we found the home of our ancestors. In that home where I spent so many happy days in my youth I have often, in later years, taken a rest from my labors with my wife and children.

Thus for me Neudeck is "home," and for my own people the firm rock to which we cling with all our hearts. It does not matter to what part of our German Fatherland my profession has called me, I have always felt myself an "Old Prussian."

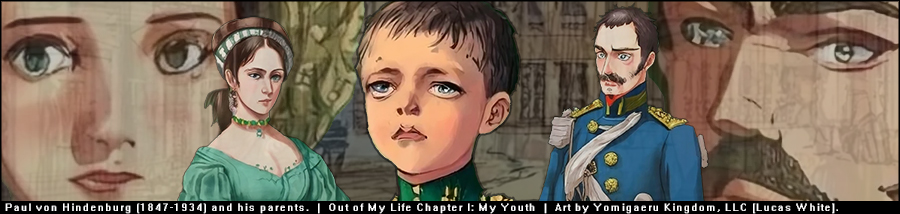

The son of a soldier, I was born in Posen in 1847. My father was then a lieutenant in the 18th Infantry Regiment. My mother was the daughter of Surgeon-General Schwichart, who was also then living in Posen.

The simple, not to say hard, life of a Prussian country gentleman in modest circumstances, a life which is virtually made up of work and the fulfillment of duty, naturally set its stamp on our whole stock. My father too was heart and soul in his profession. Yet he always found time to devote himself, hand in hand with my mother, to the training of his children — for I had two younger brothers as well as a sister. The way of life of my dear parents, based on deep moral feeling and yet directed to practical ends, revealed a perfect harmony within as without. Their characters were mutually complementary, my mother's serious, often anxious view of life pairing with my father's more peaceful, contemplative disposition. They both united in a warm affection for us and thus worked together in perfect accord on the spiritual and moral training of their children. I find it very hard to say to which of them I should be the more grateful, or to decide which side of our characters was developed by my father and which by my mother. Both my parents strove to give us a healthy body and a strong will ready to cope with the duties that would lie in our path through life. But they also endeavored, by suggestion and the development of the tenderer sides of human feeling, to give us the best thing that parents can ever give — a confident belief in our Lord God and a boundless love for our Fatherland and — what they regarded as the prop and pillar of that Fatherland — our Prussian Royal House.

From our earliest years our father also brought us into touch with the realities of life. In our garden or on our walks he wakened the love of nature within us, showed us the countryside, and taught us to judge and value men by their lives and work. By "us" in this connection I mean my next brother and myself. Of course the training of my sister, who came after this brother, was more in the hands of my mother, while my youngest brother appeared on the scene just before I became a cadet.

The soldier's nomadic lot took my parents from Posen to Cologne, Graudenz, Pinne in the Province of Posen, Glogau and Kottbus. Then my father left the service and went to Neudeck.

I do not remember much about those Posen days. My grandfather on my mother's side died soon after I was born. In 1813 he had, as a medical officer, won the Iron Cross of the combatant services at the Battle of Kulm. He had rallied and led forward a leaderless Landwehr battalion which was in confusion. In later years my grandmother had much to tell us of the "French Days" which she had known when she was a girl in Posen. I have vivid memories of a gardener of my grandparents who had once served fourteen days under Frederick the Great. In this way it may be said that a last ray of the glorious Frederickian past fell on my young self. In the year 1848 the rising in Poland had its repercussion on the province of Posen. My father went out with his regiment to suppress this movement. For a time the Poles actually got control of the city. They ordained that every house should be illuminated to celebrate the entrance of their leader, Miroslavsky. My mother was in no position to resist this decree. She retired to a back room and, sitting on my cot, consoled herself with the thought that the birthday of the "Prince of Prussia" fell on that very day, March 22, so that to her eyes the lights in the windows of the front rooms were in honor of him.

Twenty-three years later that same child in the cradle witnessed the proclamation of William I, that same "Prince of Prussia," as Emperor in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.

We did not reside very long in Cologne and Graudenz. From the Cologne period the picture of the mighty, though then still unfinished, cathedral is ever before my eyes.

At Pinne my father, in accordance with the custom then obtaining, commanded a company of Landwehr as supernumerary captain. His service duties did not make very heavy demands on his time, so that just at the very period when my young mind began to stir he was able to devote special attention to us children. He soon taught me geography and French, while the schoolmaster Kobelt, of whom even now I preserve grateful memories, instructed me in reading, writing, and arithmetic. To this epoch I trace my passion for geography, which my father knew how to arouse by his very intuitive and suggestive methods of teaching. My mother gave me my first religious instruction in a way that spoke straight to the heart.

In these years, and as result of this method of training, there gradually developed for me a relation to my parents which was undoubtedly based on unconditional obedience, and yet gave us children a feeling of what was unlimited confidence rather than blind submission to too firm a control.

Pinne is a village bounded by a manor. The latter belonged to a certain Frau von Rappard, at whose house we were frequent visitors. She had no children, but was very fond of them. Her brother, Herr von Massenbach, owned the manor of Bialakesz quite near. I found many dear playmates among his numerous family. My memories of Pinne have always remained very vivid. I visited the place when I was at Posen in the late autumn of 1914, and was greatly moved on entering the little modest house in the village in which we had once passed so many happy days. The present owner of the property is the son of one of my erstwhile playmates. His father has already gone to his long rest.

It was while I was at Glogau that I entered the Cadet Corps. For the previous two years I had attended the higher elementary school and the Protestant Gymnasium. I hear that Glogau has preserved so kindly a memory of me that a plate has been affixed to the house we then lived in to commemorate my residence there. To my great joy I saw the town again when I was a company officer in the neighboring town of Fraustadt.

Looking back over the period I have referred to I can certainly say that my early training was based on the soundest principles. It was for that reason that at my departure from the house of my parents I felt that I was leaving a very great deal behind me, and yet that I was taking a very great deal with me on the path that was opening out before me. And it was to remain thus my whole life. Long was I to enjoy the anxious, untiring love of my parents, which was later to be extended to my own family. I lost my mother after I had become a regimental commander; my father left us just before I was appointed to the command of the 4th Army Corps.

It can certainly be said that in those days life in the Prussian Cadet Corps was consciously and intentionally rough. The training was based, after true concern for education, on a sound development of the body and the will. Energy and resolution were valued just as highly, as knowledge. There was nothing narrow, but rather a certain force in this method of training. The individual should and could develop his healthy personality in all freedom. There was something of the Yorck spirit in the method, a spirit which has often been misjudged by superficial observers. Yorck was undoubtedly a hard soldier and master, to himself no less than to others, but it was he, too, who demanded unlimited self-reliance from each of his subordinates, the same self-reliance he himself displayed in dealing with everyone else. For that reason the Yorck spirit, not merely in its military austerity, but also in its freedom, has been one of the most precious traits of our army.

I have but little sympathy for the humanistics of other schools so far as they are principally concerned with dead languages. Their practical value in life has always been obscure to me. Considered as a means to an end, I am of opinion that the dead languages take up too much time and energy, and as a special study they are for the later years of life. At the risk of being pronounced an ignoramus I could wish that these schools would give greater prominence to modern languages, modern history, geography, and sports, even at the expense of Latin and Greek. Must that which was the only thing to which civilization could cling in the Dark Ages really be regarded as all-important even in modern times? Have we not, since those days, made our own history, literature, and art in hard fighting and ceaseless toil? Do we not need living tongues far more than dead ones if we are to hold our just position in world trade?

What I have said is not intended to convey any contempt of classical antiquity in itself. Quite the contrary. From my earliest years classical history has had a very great attraction for me. Roman history, in particular, had me in its grip. It seemed to me to be something mighty, almost demoniacal, and this impression possessed me particularly strongly when I visited Rome in later years, and expressed itself, inter alia, in the fact that the monuments of the ancient Eternal City appealed to me more than the creations of the Italian Renaissance.

Rome's clever recognition of the advantages and disadvantages of national peculiarities, her ruthless selfishness which scorned no method of dealing with friend or foe where her own interests were concerned, her virtuous indignation, skillfully staged, whenever her enemies paid her back in her own coin, her exploitation of all emotions and weaknesses among enemy peoples (the method which was used adroitly and with special effect in dealing with the Germanic peoples, and proved more effective than arms) — all this, as I was to learn later, found its mirror and perfection in British statesmanship, which succeeded in developing all these aspects of the diplomatic art to the highest pitch of refinement and duplicity.

But though I held the classic world in high honor I sought my youthful heroes among my own countrymen. I publicly state my honest opinion that in our admiration of an Alcibiades or a Themistocles, of the various Catos or Fabii, we ought not to be so narrow-minded and ungrateful as quite to lose sight of those men who played every bit as great a part in the history of our Fatherland as these did in the history of Greece and Rome. In this connection I am sorry to say I have often noticed, in conversation with German youths, that with all their learning there is something parochial about their outlook.

Our tutors and lecturers in the Cadet Corps guarded us against such limitation of vision, and I thank them for it now. My thanks are due more especially to the then Lieutenant von Wittich. I had been recommended to him by a relation of mine when I first went to Wahlstatt, and he always took a particularly friendly interest in me. He had left the Cadet Corps himself only a few years before, and he regarded himself as quite one of us, gladly took part in our games, especially snowballing in winter, and was a man of character and ideas. Above all he possessed a wonderful talent for teaching. In 1859 he taught me geography in the lowest form, and six years later he taught me land survey in the special class in Berlin. When I attended the Kriegsakademie some years after I found that Major von Wittich of the General Staff was once more one of my tutors.

Wittich was interested in military history even in his lieutenant days, and on our walks on fine days often set us little exercises in suitable spots to illustrate the battles which had just been fought in Upper Italy — Magenta and Solferino, for example. Later, in Berlin, he encouraged me, now a cadet, to take up the study of military history, and aroused my youthful interest in railways, which was important for my future progress. Who can doubt that military history is the best training for generalship? When I was subsequently transferred to the General Staff, Lieutenant-Colonel von Wittich was still attached to it in an important position, and finally we were simultaneously appointed G.O.C.'s — that is, to the command of an Army Corps. The little lowest-form boy at Wahlstatt hardly suspected that when Lieutenant von Wittich gave him a friendly whack with a ruler because he mixed up Mont Blanc and Monte Rosa.

Our high spirits did not suffer from the hard schooling of our cadet life. I venture to doubt whether the boyish love of larking, which no doubt at times reached the stage of frantic uproar, showed to more advantage in any other school than among us cadets. We found our teachers understanding, lenient judges.

At first I myself was anything but what is known in ordinary life as a model pupil. In the early days I had to get over a certain physical weakness which had been the legacy of previous illnesses. When, thanks to the sound method of training, I had gradually got stronger, I had at first little inclination to devote myself particularly to study. It was only slowly that my ambitions in that direction were aroused, ambitions which grew with success, and finally brought me, through no merit of mine, the calling of the specially gifted pupil.

Notwithstanding the pride with which I styled myself "Royal Cadet," I hailed my holidays at home with uncontrollable delight. In those days the journeys, especially in winter, were anything but a simple matter. According to one's destination, slow journeys in a train (the carriages were not heated) alternated with even slower journeys in the mail-coach. But all these difficulties took a back seat compared with the prospect of seeing my home, parents, and brothers and sister again. Her son's longing for home filled my mother's heart with the deepest joy. I can still remember my first return to Glogau for the Christmas holidays. I had been travelling with other comrades in the coach from Liegnitz the whole night. We were delayed by a snowstorm, and it was still dark when we reached Glogau. There, in the so-called "waiting-room," badly lit and barely warmed, my dear mother was sitting knitting stockings just as if, in her anxiety to please one of her children, she were afraid of neglecting the others.

In my first year as cadet, the summer of 1859, we had a visit at Wahlstatt from the then Prince Frederick William, later the Emperor Frederick, and his wife. It was on this occasion that we saw for the first time almost all the members of our Royal House. Never before had we raised our legs so high in the goose-step, never had we done such break-neck feats in the gymnastic display which followed as on that day. It was a long time before we stopped talking about the goodness and affability of the princely pair.

In October of the same year the birthday of King Frederick William IV was celebrated for the last time. It was thus under that sorely tried monarch that I put on the Prussian uniform which will be the garb of honor to me as long as my life lasts. I had the honor in the year 1865 to be attached as page to Queen Elizabeth, the widow of the late King. The watch which Her Majesty gave me at that time has accompanied me faithfully through three wars.

At Easter, 1863, I was transferred to the special class, and therefore sent to Berlin. The Cadet School in that city was in the new Friedrichstrasse, not far from the Alexanderplatz. For the first time I got to know the Prussian capital, and was at last able to have a glimpse of my all-gracious sovereign, King William I, at the spring reviews when we paraded on Unter den Linden and had a march past in the Opernplatz, as well as the autumn reviews on the Tempelhofer Feld.

The opening of the year 1864 brought a rousing, if serious atmosphere into our lives at the Cadet School. The war with Denmark broke out, and in the spring many of our comrades left us to join the ranks of the fighting troops. Unfortunately for me I was too young to be in the number of that highly envied band. I need not try to describe the glowing words with which our departing comrades were accompanied.

We never troubled our heads about the political causes of the war. But all the same we had a proud feeling that a refreshing breeze had at last stirred the feeble and unstable structure of the German union, and that the mere fact was worth more than all the speeches and diplomatic documents put together. For the rest we followed the course of military events with the greatest eagerness, and, quivering with excitement, were joyful spectators when the captured guns were paraded round and the troops made their triumphal entry. We thought we were justified in feeling that within us resided something of that spirit which had led our men to victory on the Danish battlefields. Was it to be wondered at that henceforth we were all impatient for the day on which we ourselves would enter the army?

Before that day came we had the honor and good fortune to be presented personally to our King. We were conducted to the castle, and there had to tell His Majesty the name and rank of our fathers. It is hardly surprising that many of us, in our agitation, could not get a word out at first, and then poured them out pell-mell. Never before had we been so close to our old sovereign, never before had we looked straight into his kind eyes and heard his voice. The King spoke very earnestly to us. He told us that we must do our duty even in the hardest hours. We were soon to have an opportunity of translating that precept into action. Many of us have sealed our loyalty with death.

I left the Cadet Corps in the spring of 1865. My own personal experiences and inclinations throughout my life have made me grateful and devoted to that military educational establishment. It is a joy to think of my hopeful young comrades in the King's uniform. Even during the World War, I was only too happy to have an opportunity of having sons of my colleagues, acquaintances, and fallen comrades as guests at my table. A more favorable occasion, the celebration of my seventieth birthday, which fell during the war, gave me an opportunity of beginning the ceremonies by having three little cadets brought out of the streets of Kreuznach to my lunch table, piled high with edible gifts. They came in before me cheery and unembarrassed, exactly as I would have boys come, the very embodiment of long-past days, living memories of what I myself had been.